The Chichester SMR holds information for 48 sites, whilst the National Monuments Record

Centre holds details of a further 16 sites within the study area. An additional four sites were

located through analysis of historic mapping and during the course of the walkover survey and

one from aerial photographs. Full site descriptions and locations can be seen in Appendix B.

Within the report, the bracketed numbers after site descriptions relate to those allocated to

individual sites in Appendix B and on Figure 2.

Only one Scheduled Monument is located within the study area. This is the Chichester

defensive entrenchments dating to the Iron Age period (1).

There are eight listed buildings within the study area. Two buildings, the Chichester Festival

Theatre and Royal and West Sussex Hospital, are designated Grade II*. The others all

designated Grade II listed.

There are two Conservation Area within the study area. The Chichester Conservation Area lies

along the southern boundary of the site and the Grayingwell Hospital Conservation Area is

positioned directly to the east of the barracks. The Graylingwell Hospital also falls within a

Grade II Registered Park. The boundaries of these features can be seen on Figure 2.

There are no World Heritage Sites or Registered Battlefields within the study area.

Prehistoric (to 43 AD)

Very few previously recorded sites dating to the prehistoric period are known within the study

area. One Palaeolithic (to c. 10,000 BC) hand axe (19) was recovered from a garden on

Brandyhole Lane. No further dated evidence is recorded until the Neolithic period (c. 3500BC to

2600 BC). This comprises the find spot of a stone axe (12). No artefacts from the intermediate

Mesolithic period (c. 10,000 BC to 3500BC) have been recovered.

The first true indication of settlement in this area dates to the Bronze Age (c. 2800BC – 800BC).

Four previously recorded sites have been recorded within the study area. Possible evidence of

settlement was found just to the north of Graylingwell Hospital (57) as well as the remains of six

cremation burials (51) dating to the middle Bronze Age. Further evidence to support this has

been found in the form of a Bronze palstave1 (13) and a barbed and tanged arrow head (39)

recovered from a garden.

The first major features in the area date to the Iron Age (800BC – 43AD). The Scheduled

Monument within the study area is the Chichester Dykes or entrenchments (1). This defensive

system of ditches date to later in the Iron Age period which was a time of unrest between the

tribes of England. One section of these entrenchments are believed to follow the alignment of

The Broadway, the road which borders the development site to the north.

Other features from the Iron Age have also been identified within the study area. During works

at Graylingwell Hospital excavations identified sections of the entrenchments. Just within its line

an enclosure which may indicate the position of a settlement (52) was identified while two

earthenware pots with cremated bones were recovered from just outside the entrenchment

(43). Shards of pottery from this period have also been recovered from an excavation at the

rear of Cawley’s Almshouses (23).

No features dating to the prehistoric period have been identified within the site boundary.

Roman (43AD– 450 AD)

One of the key periods within this area is the Roman occupation. When the Romans came to

this area the local ruling tribe co-operated rather than resisted, which allowed them to retain

1 A bronze axehead of middle or late Bronze Age date in which the side flanges and the

bar/stop on both faces are connected, forming a single hafting aid.(Source:

http://thesaurus.english-heritage.org.uk/)

3 Results

Faber Maunsell Roussillon Barracks, Chichester 10

some control in the area. The Romans built a fort where the modern city now stands and when

they moved on the local tribe took control and developed it into a town, Noviomagus. In the 2nd

century a defensive ditch was placed around the town with a wooden palisade. Later these

wooden defences were replaced with a stone wall, bastions and towers

(http://www.localhistories.org/chichester.html). Chichester had many of the recognisable

elements of many Roman towns across Europe including an amphitheatre, public baths and

temples.

The proposed development site falls outside of the defensive walls of the Roman town.

However, evidence form the study area suggests that occupation was not confined to within

these walls. There are five recorded sites within the study area with evidence of Roman

settlement (20, 24, 44, 53, 55). This evidence includes pottery, tile and masonry and one site

excavated in 2001 identified remains of a timber cill-beamed building (24). Evidence such as

Roman water pipes (25), ditches (25, 58), a possible kiln (64) and several coins (36, 38, 46, 47)

help to illustrate the level of settlement in this area.

Two sites show the burial practises dating to this period. The St Pancras Roman Cemetery (20)

lies in the southern section of the study area just outside the east gate. The excavation at

Cawley’s Almshouses in 1998 also identified two urns containing burials (42) also dating to the

Roman period.

The alignments of two roads dating to this period are also believed to cross the study area. The

first runs 39 miles from Chichester to Silchester (10) and was identified from aerial photography

by the Ordnance Survey (Margary 1967, 78). The road left Chichester at the north gate and ran

north-westerly through the study area to the west of Broyle Road. Sections of this road have

been identified at different times during excavation. The second suggests that the line of St

Paul’s Road (63) running north-west out of the city may also be a Roman road however there is

less evidence to support this.

No features from the Roman period have been identified within the site boundary.

Early Medieval (450 AD – c. 1066)

There are two site of early medieval date recorded within the study area. The first is the site of

Chichester Priory (11) located to the south of the study area. The Priory, which possibly had a

minster and double house, was founded c. 956 and a Benedictine nunnery was later added

prior to 1066. The Priory was dissolved in 1075. The only other evidence dating to this period

was an early Saxon spearhead (34) found in a garden of a house just to the north of the

proposed development area.

No features from the early medieval period have been identified within the site boundary.

Medieval (c.1066 – 1500)

There are two known and one possible additional site of medieval date recorded within the

study area. This period was also important for the development site itself. One road, the

Chichester to Hindhead trackway (54), ran to the east of the development sites and a ditch was

identified during an archaeological excavation.

The development site itself is documented as forming part of a deer park during the medieval

period. The place name ‘Broyle’ refers to an area of forest enclosed by walls or ditches and

possibly stocked with animals for hunting. The land was owned by the king but was granted to

the Bishop of Chichester by Henry II. The Manor Broyle remained in the church ownership and

appears to have remained as moor land until it was purchased for the purpose of developing a

barracks on the site in the 18th century.

Post-Medieval (c.1500 AD – 1900 AD)

Chichester continued to expand during the post-medieval period as the population continued to

increase. A number of recorded sites within the study area relate to the development of the

town and the growth of farming practises in the wider area. The Plan of the Manor of Broyle

from 1772 and Glot’s survey from around the same time (see Figure 3) shows that much of the

land to the north of Chichester had been divided into field systems. The area named as ‘The

Broile’ is defined by the same boundaries as the proposed development site and is shown on

the map as open moorland, with one farm with a defined field and formal garden at the southern

end of the site. The farm is believed to be later subdivided into 29 and 31 Wellington Road

Faber Maunsell Roussillon Barracks, Chichester 11

which are now Grade II listed buildings. Two windmills (35, 37) and two wells (18, 41) are

recorded within the study area which may relate to the farming practices being undertaken.

The two maps discussed above, and subsequent editions of the Ordnance Survey maps, also

make reference to the town gallows and an obelisk being located on the southern section of the

development site. A commemorative stone once stood on the site marking the location of the

gallows and recounting the story of the “Halkhurst Gang”, a member of which is recorded to

have been buried in the field adjacent to the gallows. This stone and obelisk were relocated in

later years when the barracks became a secure site. The stone with information about the gang

now stands outside of the wall on Broyle Road (see Photograph 1) and the obelisk is positioned

adjacent to the southern gate on Wellington Street (see Photograph 2). The inscription on the

stone can be seen in Appendix C (Keating. 1979. 59).

The 1846 Tithe Map of St Peter the Great records the two key areas of the development site as

being owned by the Barracks Department with the field names given as “The Barracks” and

“Gallows Field”. There are no structures associated with the barracks depicted on the mapping

at this time suggesting that accommodation at this time was in the form of tents. Records show

that the land was built on between 1795 and 1813 at the cost of £76,167 on land purchased

from the Bishop of Chichester. The Hampshire Telegraph followed the stages of building on the

site in 1803 by French Prisoners of War and recorded (www.army.mod.uk):

21 Feb – Barracks occupied by the barracks master and family

1 Aug - 100 men building new cavalry Barracks on the Broil

5 Sep - Work proceeding rapidly to accommodate 1500 men

21 Nov - Nearly finished.

Numerous cavalry and infantry units were stationed at the barracks throughout the 19th century

and a plan of the barracks from 1859 (Entec, 2007) shows that much of the layout of the

barracks is in place by this time with the northern section of the site occupied by small

structures for accommodation, the parade ground laid out and a hospital present in the south

east corner of the site.

In 1873 the barracks became the regimental station for the Royal Sussex Regiment. They had

been formed in 1701 and had served in a number of campaigns including the defeat of the

French Royal Roussillon Regiment in 1759 which would go on to lend its name to the barracks

in 1958.

The next major stage of development was in 1875 when some of the wooden structures were

replaced by brick buildings including the Keep and the Chapel and the site was enclosed by the

flint and brick wall which is extant (see section 3.2 below).The Ordnance Survey map of 1875

(see figure 4) shows the layout of the barracks, the fact that the surrounding area was still

undeveloped and that the northern boundary of the site was defined by a section of the Iron

Age entrenchments where The Broadway now runs. The hospital is clearly marked on the map

as a small grouping of buildings with a driveway. Several buildings are located along Broyle

Road including canteen, guardhouse, stores and a magazine.

A number of buildings that may be expected on the outskirts of a town are within the study

areas and demonstrate how Chichester grew in this period. A lime kiln (41) is located along

Broyle Road at a safe distance from the walls. Establishments such as the work house (16), the

Graylingwell Lunatic Asylum (17) and the hospital were all in easy reach of the city but out of

public view.

Most of the listed buildings within the study area date to the post-medieval period. Only three of

the buildings, two on Wellington Road (7 and 8) and a small row of terrace houses on Broyle

Road are adjacent to the proposed development site.

Modern (1900 AD - Present)

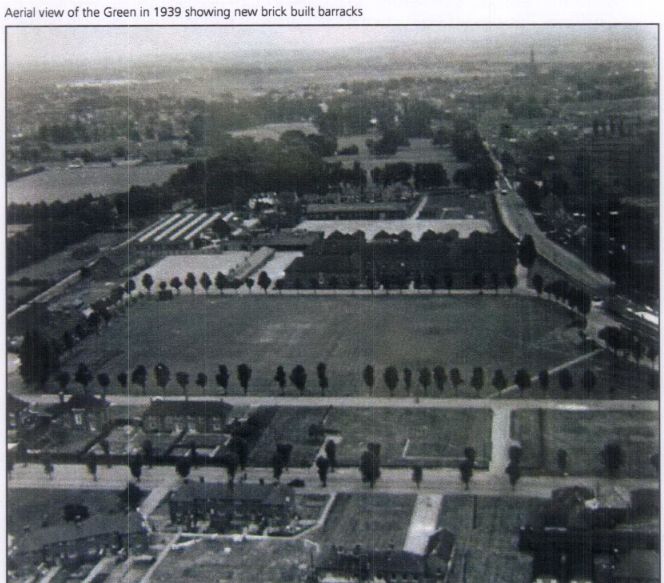

Further development of the site was undertaken in the 1930s which included the construction of

the Sandhurst Block and some of the accommodation to the north of the parade ground. The

Royal Sussex Regiment were merged with the Home Counties Brigade in 1960 and moved to

Canterbury. At this time the barracks were taken over by the Royal Military Police and another

stage of building work was undertaken. An Officer’s Mess, Sergeant’s Mess, training facilities

Faber Maunsell Roussillon Barracks, Chichester 12

and an assault course, some of which are depicted on the 1963 OS map (see figure 5), were

constructed.

Many of the previously recorded sites dating to this period are also linked to the military.

Several examples of World War II defences are known in the area. Tank traps and ditches (21,

61 and 62) as well as concrete blocks (28, 31 and 41) were positioned to protect approaches to

the city.

One listed building, the Grade II* Chichester Festival Theatre also dates to the modern period.

Whilst the proposed development site remained under military control the rest of the study area

was gradually incorporated into the urban development of Chichester, with housing surrounding

the site to the west and north and open parkland being retained to the south and east.

The areas directly to the east and south of the proposed development site fall within the

Chichester and Graylingwell Conservation Areas. The Conservation Areas have been

designated due to their special architectural or historic interest which requires preservation or

enhancement (www.chichester.gov.uk).

Unknown Date

There are two sites of unknown date within the study area. In two locations (29 and 32) layers

of gravel have been noted during drainage and construction works. The exact nature of these

layers in unknown